We designed FDM-1, a foundation model for computer use. FDM-1 is trained on videos from our 11-million-hour screen recording dataset, labeled with an inverse dynamics model. It’s consistently improving at task completion as we scale it, and is the first model with the necessary components to become a general coworker for CAD, finance, data, and eventually ML engineering. FDM-1 trains directly on 30 FPS video instead of screenshots and, like OpenAI’s GPT, can learn unsupervised from the entirety of the internet.

Figure 1: Diagram of the FDM-1 training recipe

The current recipe for building computer use agents is to finetune a vision-language model (VLM) on contractor-labeled screenshots of computer use, then build RL environments to learn each specific downstream task. However, VLMs are hobbled by their limited context windows: they can’t train or act on more than a few seconds of context. This prevents them from processing high-framerate video, training on long horizon tasks, or scaling to competent, general agents.

Training these chain-of-thought VLMs requires contractor-labeled annotations. This is expensive, so current computer action datasets are tiny: the largest open dataset uses only 355,000 unique screenshots and 19,000 action trajectories—less than 20 hours of 30 FPS video. Meanwhile, millions of hours of video of film editing, coding livestreams, video game playthroughs, and more have been accumulating on the internet for the past two decades. Building a general computer agent requires an internet-scale video corpus, just as GPT-3 was only possible with an internet-scale text corpus.

To train on all this video, you need to label it with actions. Prior literature has explored this direction; The behavior cloning from observation paper teaches an inverse dynamics model (IDM) to predict what action was taken between before states and after states in various simulated environments. IDM-labelling is tractable for computer use datasets because mouse movement and typing actions are often easily inferable from the screen; if a “K” shows up, you can be reasonably confident the “K” key was pressed. [1] 1. There are technically other ways (e.g. a ctrl+v from an earlier ctrl+c) but looking at minutes of history lets us accurately label long-range inverse dynamics, so we can have high confidence in the sequence of actions that produced a given computer state for almost any video. OpenAI’s Video PreTraining (VPT) paper was the first to apply this method at scale, bootstrapping a Minecraft-specific IDM on a small amount of contractor data to create a competent Minecraft agent with six seconds of context. [2] 2. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.19 VideoAgentTrek also trained a computer action IDM to label data. The key problem here is they don’t have video context (cannot do Blender or any continuous tasks) and instead rely on screenshot-action-CoT triplets.

VPT’s architecture was able to learn complex behaviors—playing Minecraft—something still inaccessible to VLM-based approaches. Unlike Minecraft, however, capable computer use requires not just six seconds, but minutes to hours of context.

The missing piece is a video encoder. VLMs burn a million tokens to understand just one minute of 30 FPS computer data. By leveraging the inherent redundancy in screen recordings, our video encoder encodes nearly two hours of video in the same number of tokens—this is 50x more efficient than the previous state-of-the-art and 100x more efficient than OpenAI’s encoder. This improvement in context length and data scale opens the path to finally pretrain on enough video to scale generally competent computer action models.

Training Recipe

Our training recipe consists of three stages (see Figure 1). First, we train an IDM on contractor-labeled screen recordings. Second, we use the IDM to label our 11-million-hour video corpus. Finally, we use this IDM-labeled video corpus to autoregressively train a forward dynamics model (FDM) on next action prediction. The FDM’s output token space consists of keypresses and mouse movement deltas, which are expressive enough to model any actions taken on a computer.

Figure 2: A chart comparing the amount of frames our tokenizer can fit in a 200k-token context window. We estimate tokens for GPT & Gemini from API documentation. [3] 3. Gemini was taken from the documentation (200,000/258= ~775). ChatGPT Computer use was taken from vision documentation with a 720x1280 screen with tile size 768 (32=6; (6129)+65=839; 200,000/839=~240. NVIDIA Cosmos CV4x8x8 was taken from the model card (1280/8) × (720/8) =160 × 90=14,400; 200,000/14,400 =13×4 =~49 input frames.

Underlying both the IDM and our FDM is our state-of-the-art video encoder, which lets us compress almost 2 hours of 30 FPS full-resolution video data into a 1M token context window.

Video Encoder

Videos of the real world and bodies of text both have relatively uniform information densities throughout, and both can be compressed into a latent representation without losing much semantic content. [4] 4. Generative video models don’t need to see every detail of text on the screen, so they can compress to a very high degree without worrying nearly as much about losing information. Screen recordings are different: information density can vary rapidly. There is a massive information difference between moving a cursor across the screen and scrolling through pages of text. Existing approaches with fixed-size embedding spaces over fixed amounts of time inevitably trade off between space needed to store full fidelity text and context compression ratio.

| Context Length | 30 FPS Video |

|---|---|

| 32k tokens | 3 minutes 30 seconds |

| 200k tokens | 20 minutes |

| 1M tokens | 1 hour 40 minutes |

Table 1: Showing how much video we can fit in certain context windows for our model [5] 5. With additional research, higher compression multiples are likely possible.

We created a model without this tradeoff by training our video encoder on a masked compression objective. [6] 6. The https://ai.meta.com/research/vjepa/ paper is similar, but not exactly what we used to enrich our video frame embeddings. We used the core thesis of having a self-supervised prediction task to create expressive embeddings. This unsupervised training enables our encoder to produce information-dense features at a high compression rate. Due to our use of an unsupervised training method, we use downstream tasks to measure the perceptual and semantic abilities of our encoder. These tasks include parts of our training recipe, like inverse dynamics and action prediction, as well as synthetic benchmarks like adding a probe for frame reconstruction or random text transcription to give specific signals.

We ablate representations from our video encoder to a standard ViT; we observe ~100x faster convergence compared to baselines (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Accuracy on a transcription task. Baseline was a basic ViT over raw frame data, controlled for the number of transcription tokens seen (w/ similar FLOPs).

Our encoder achieves a state-of-the-art compression ratio of video frames to tokens, as shown in Table 1. Our 30fps video context unlocks long-horizon workflows such as CAD, while still maintaining the ability to read text on the screen with high fidelity.

Inverse Dynamics

In order to train on orders of magnitude more labeled data than contractors can provide, we need to automatically label the whole internet with predicted computer actions—mouse movements, keypresses, etc.. We created an IDM to predict high-quality labels, letting us achieve similar efficiency from arbitrary videos as human-gathered ground truth data.

Labeling video is fundamentally non-causal—you can’t label a Cmd+C until you see the resulting pasted sequence. [7] 7. After experimenting with CTC loss as well as normal cross entropy for inverse dynamics modelling, a masked diffusion model performed best. To train a non-causal, generative model, we adopted a masked diffusion architecture. For more on masked diffusion training and how it works, see [8] 8. Generative modelling is important to scaffold the action space correctly. When using a non-causal cross-entropy metric, typos were extremely common. ">https://s-sahoo.com/mdlm [8] 8. Generative modelling is important to scaffold the action space correctly. When using a non-causal cross-entropy metric, typos were extremely common.

Our diffusion method predicts actions conditioned on all frames simultaneously with masked action tokens. During inference, we feed frames interleaved with mask tokens and have the model predict log probabilities for each masked position. We then select the top-k highest-confidence predictions, unmask those tokens, and repeat until the full sequence is labeled.

This way, we can engineer the model to spend baseline effort on high probability actions (by labeling them first) and more effort on ambiguous ones, leading to more accurate labels. This non-causal approach was also more data efficient, overfitting significantly slower than causal models.

Forward Dynamics

The FDM predicts the current action conditioned on prior frame and action history. [9] 9. Labelled data isn’t strictly necessary for prediction because of the near-determinism of computer environments. We exploit this for small-scale experiments, masking action events to slow overfitting. Unlike VLM-based approaches, our model operates directly on video and action tokens—no chain-of-thought reasoning [10] 10. We still have transcription tokens during training, mainly for instruction tuning downstream and general language grounding. This is still extremely different from chain-of-thought data because most actions do not have a transcript preceding them. Overall we have ~1.25T transcript tokens or language-level token compression (i.e., BPE, tool use typing). This keeps inference low-latency and ensures the model sees the same distribution at inference time as during training.

To enable autoregressive modeling of continuous mouse movements, we convert frame-to-frame changes in cursor position (“mouse deltas”) into discrete tokens. First we normalize a mouse delta relative to screen width and height, and then separate the X and Y axes. Each axis is tokenized independently using exponential binning over 49 bins ((0,7], (7,25], (25,75], etc.). Such a scheme accurately describes small, frequent movements while still covering large, infrequent movements with coarser bins.

We also train with multi-token prediction auxiliary losses for mouse click prediction. These auxiliary losses showed promise on small-scale synthetic tasks.

Language understanding is difficult for our model since we pretrain at the character level. In future work we plan to explore methods for transferring knowledge from language models. Without transfer, we still see promising improvement on tasks like email composition and document writing.

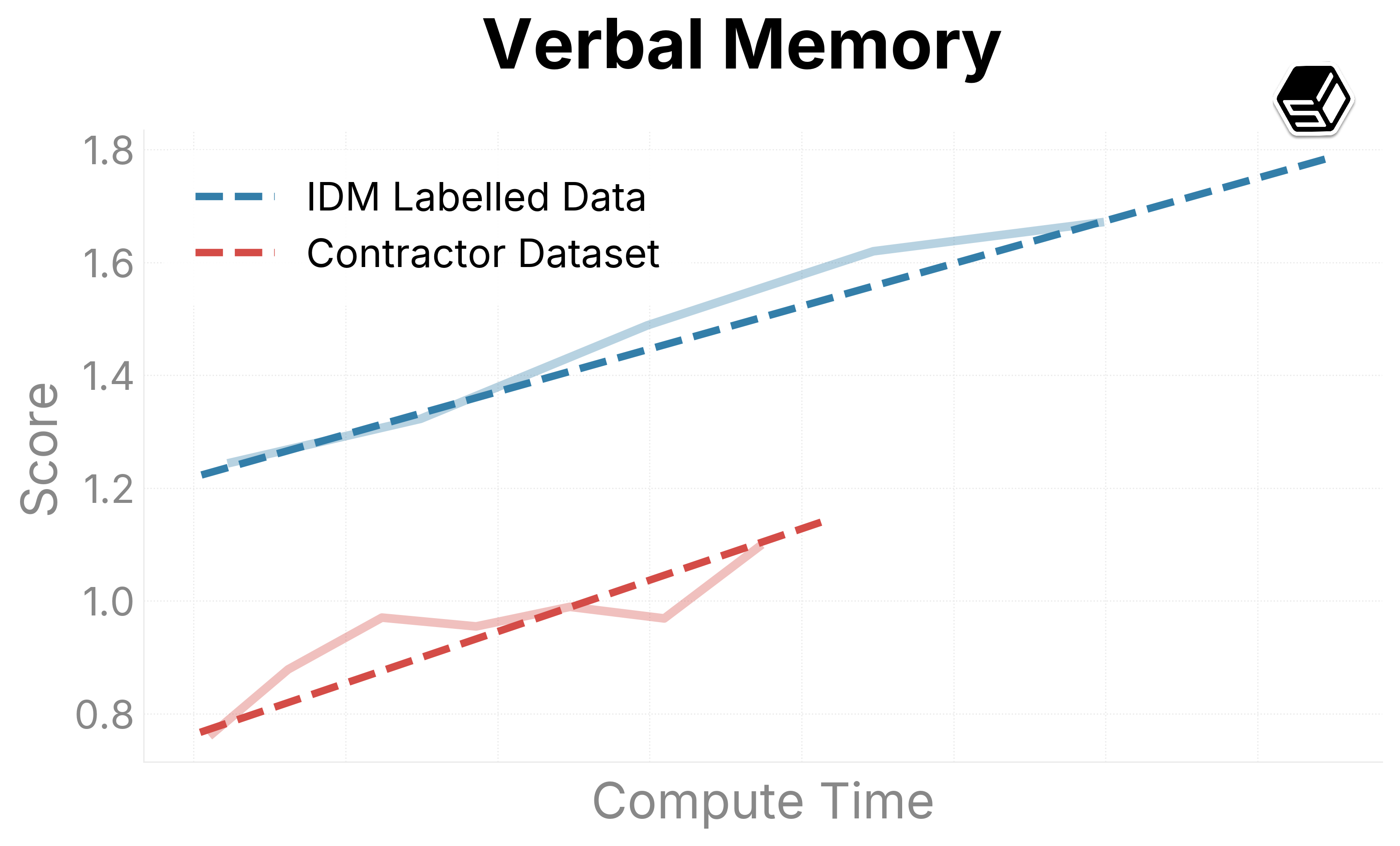

A key question for our recipe is whether IDM-labeled data is effective enough to substitute for ground-truth contractor data at scale. Our training loss curves show that IDM-labeled and ground-truth data produce comparable learning dynamics, suggesting that the noise introduced by IDM labeling does not significantly degrade training signal. More details can be found in the evaluation section.

Evaluations

Evaluating an action model requires running it in live environments at scale. Using forking virtual machines (VMs), we built eval infrastructure that supports ~1M rollouts/hour with about 80,000 VMs. Each VM is a minimal Ubuntu desktop environment with 1 vCPU and 8GB of RAM; a single model instance served on an H100 can control 42 of these in parallel.

Forking lets us capture a full memory snapshot of an OS state and replicate it onto a fresh VM without corrupting the base environment. This allows us to reuse a single evaluation starting state, faithfully, across thousands of rollouts.

Our VM inference framework is also effective at masking latency such that the model is in distribution during inference. Inference time latency can induce a distributional shift from the pretraining distribution: even one second delays result in stale observations conditioning the model’s generated actions. We mitigate this through a variety of methods: colocating the GPUs and VMs in the same cloud region, using cumulative sequence length packing for VMs at different times, a low latency VNC configuration, and utilizing Rust bindings for device input. All of these let us achieve a round trip screen capture to action latency of 11ms.

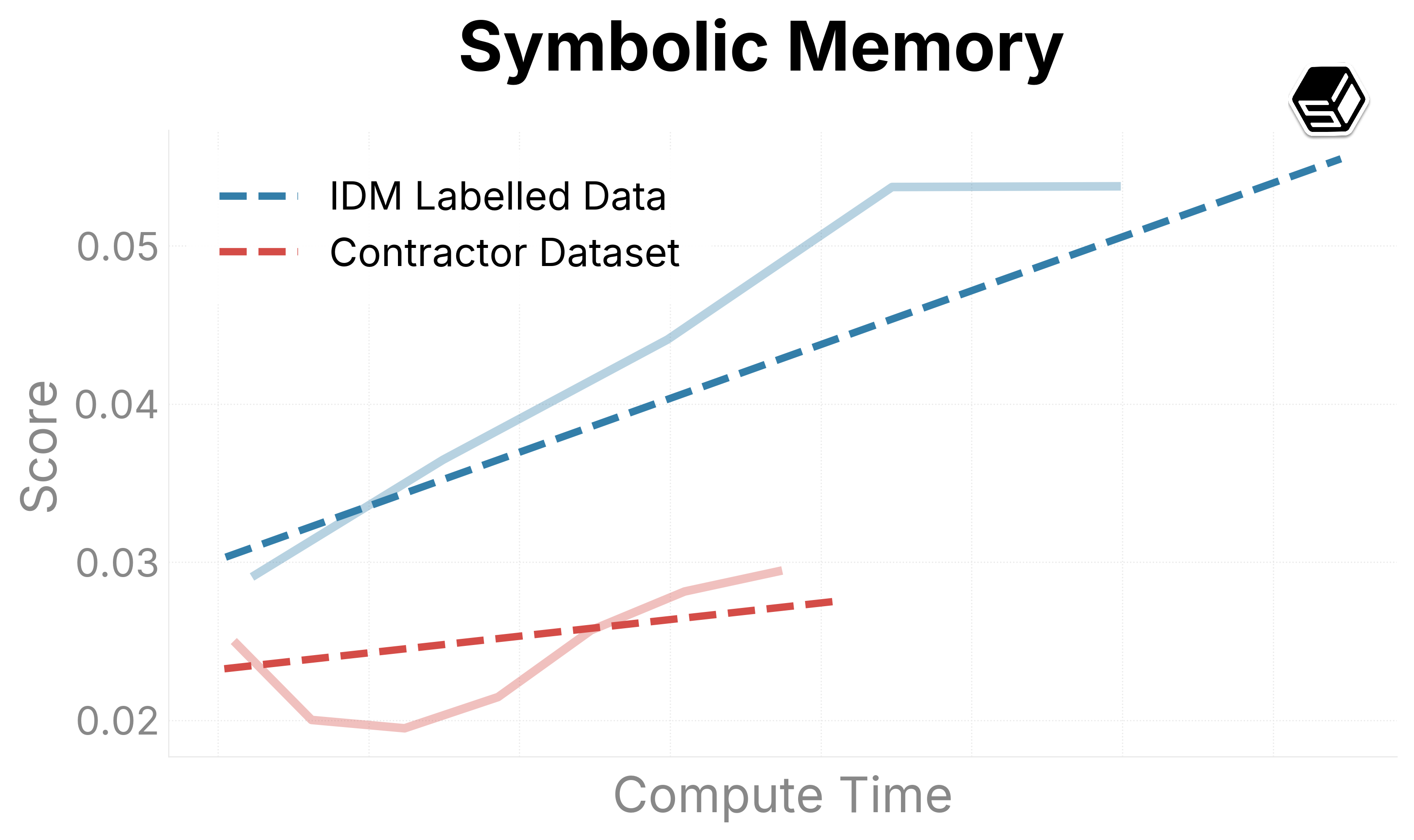

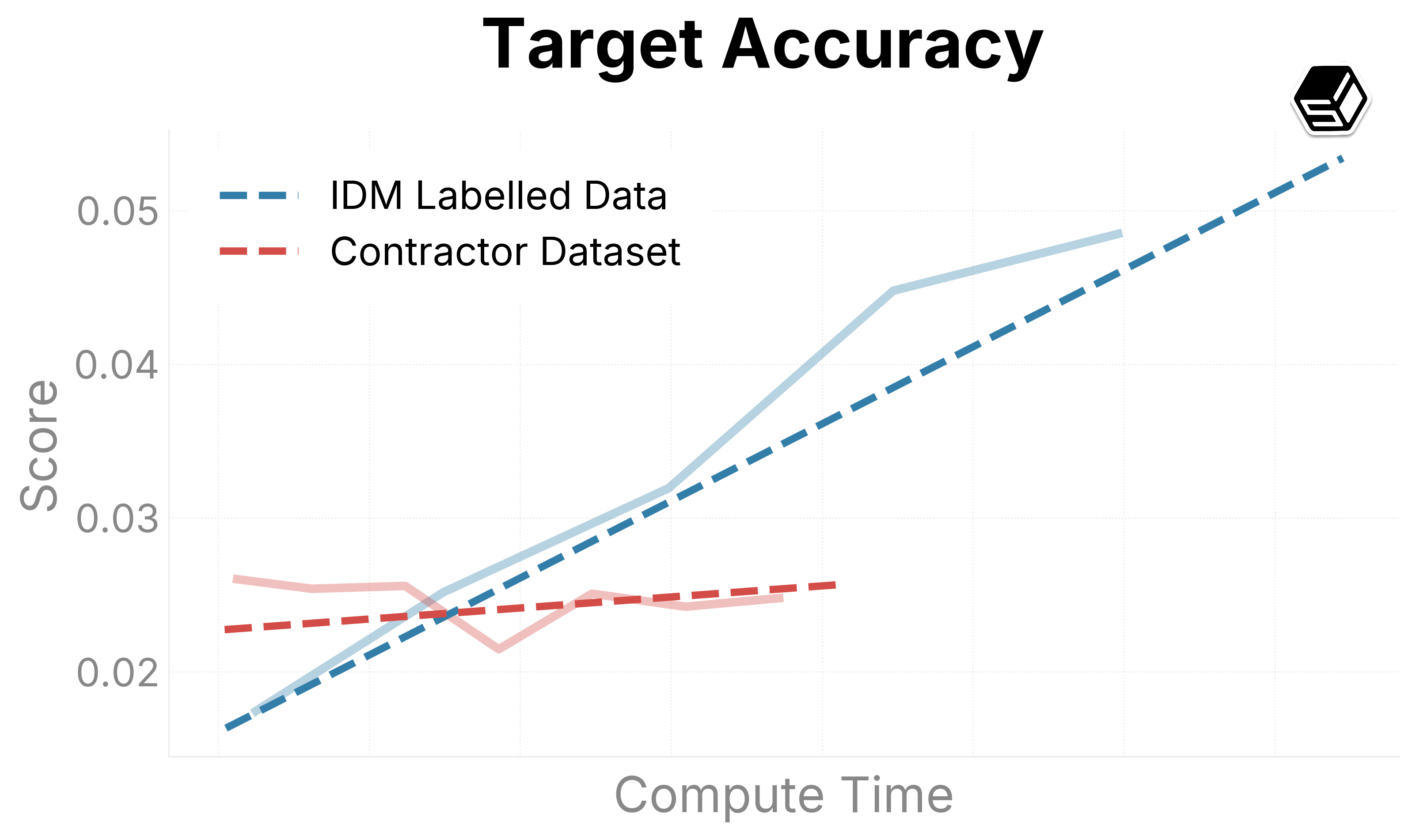

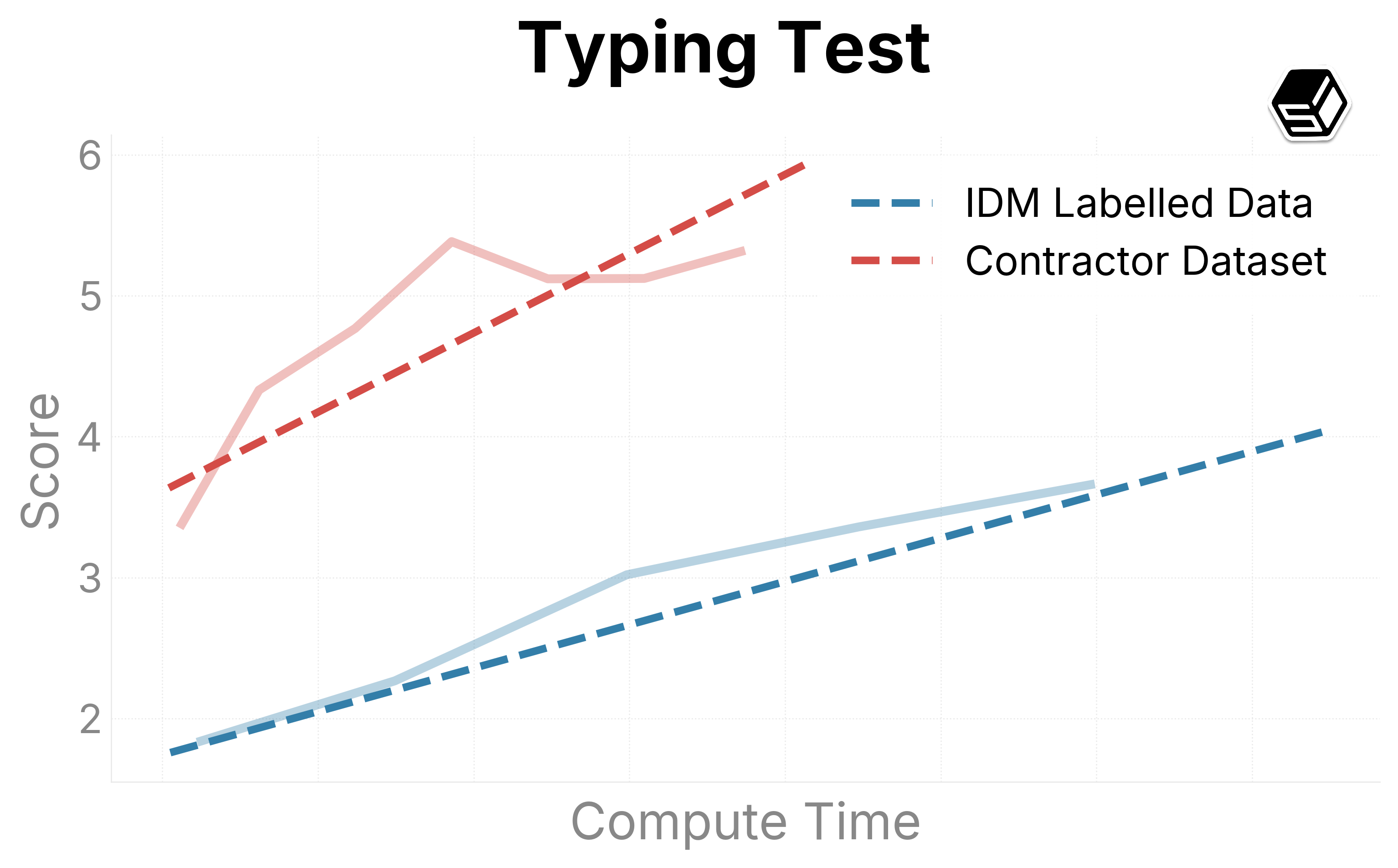

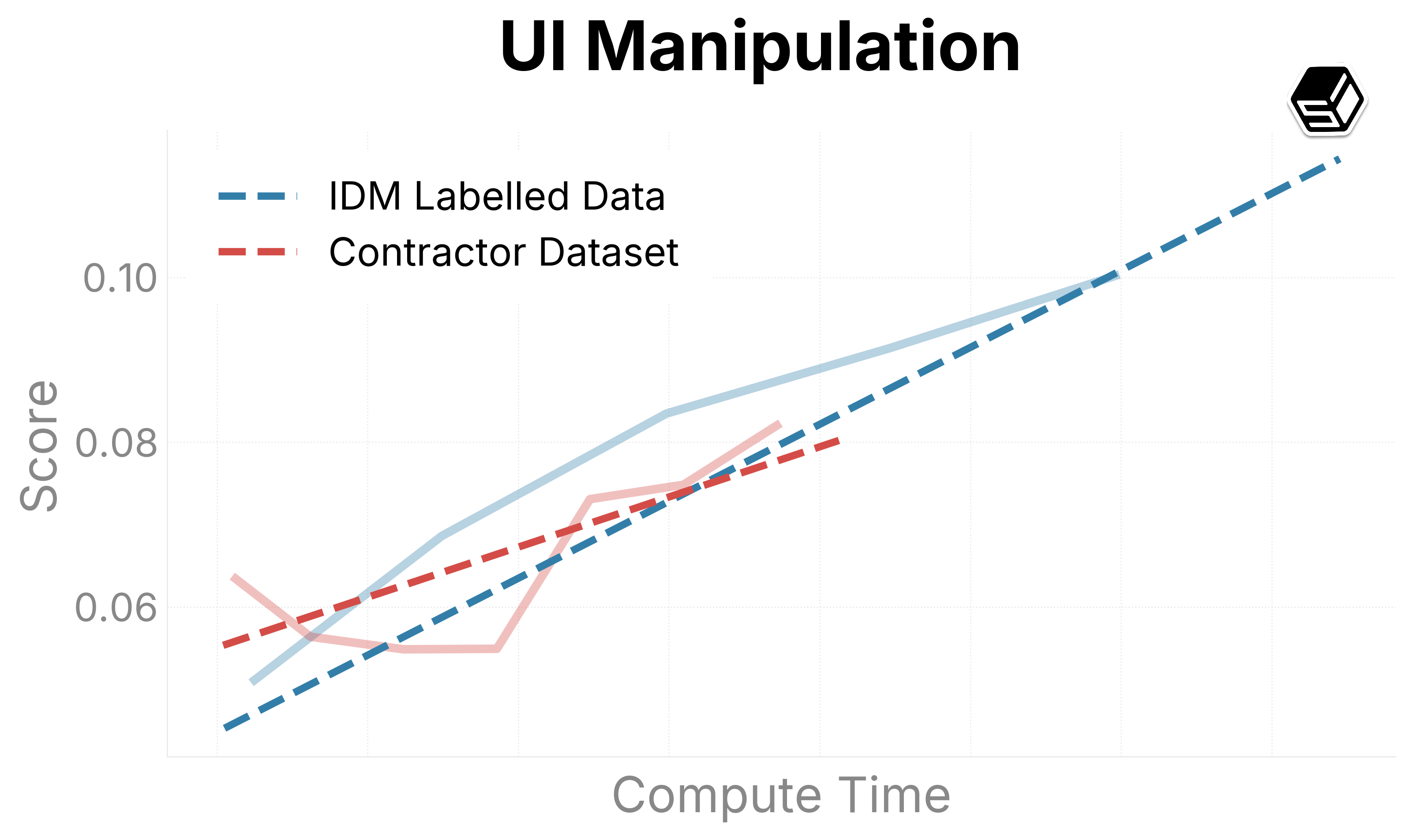

We present promising early trends on our internal evaluation suite (Figure 6). Ground-truth contractor data is compared with the IDM dataset to both determine the quality of the IDM dataset and determine scaling trends when increasing run sizes. The IDM split usually outperforms our contractor dataset in general capabilities regarding mouse movement and action.

For typing and verbal understanding, our IDM dataset has positive progress but slower. We predict this is because of the noise introduced from the IDM, leading us to consider including a contractor mix of the dataset while scaling up the model.

Demos

Computer Aided Design

As we scale our recipe, our model learns to complete human computer action trajectories. Our internal evaluation suite consists of OS states paired with “few-shot prompts:” a human-generated frame-action sequence that corresponds to a complex behavior like object segmentation, 3D manipulation, etc. With scale, our model’s success rate at successfully inferring human behavior increases smoothly, indicating its promise at being a “copilot for computer use.” Below is a video of a rollout successfully extruding faces on an n-gon to make a gear in Blender. [11] 11. Note this video was generated with our forking VM infrastructure, checkpointing at each successful extrusion.

Automated UI Testing

Our model is unusually capable at “fuzzing” GUIs—finding bugs that require deep exploration of the state tree or strange GUI interactions. This is because the model is working with a general prior. We demonstrate this in a toy environment where we use our forking VM infrastructure to explore as many unique states as possible in a banking app, forking when a meaningfully new state has been explored. The model finds a bug where the Submit Wire Transfer button is clickable right after a wire transfer has already been completed, allowing balance to go negative.

Self-Driving

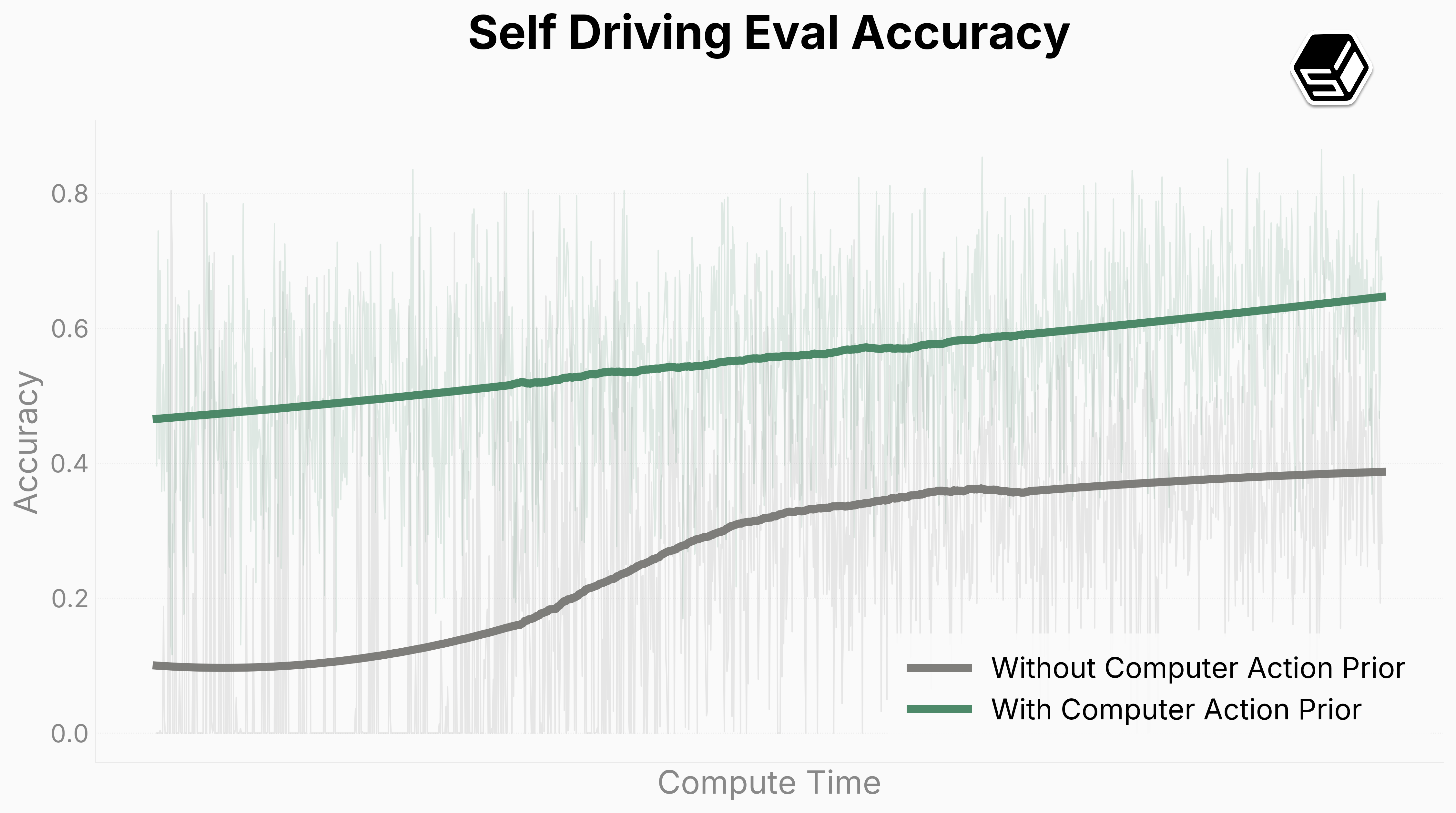

Since FDM-1 was trained on general internet video, including game data, we wanted to check transfer onto real world tasks. Self driving seemed like the perfect test of generality and continuous motion in 30hz. To achieve this we finetuned our model to autosteer around our block.

We connected a comma running openpilot in “Joystick Mode” to a web app—this app included arrow keys to control the wheel as well as proprioceptive state for steering angle, brake state, and acceleration state. Through the web app, we collected ~1hr of demonstration data and finetuned FDM-1. We present a demonstration of it driving and making turns autonomously below!

We demonstrate that our priors from computer action generalize to the real world significantly more than a model without such priors. This indicates that future models could push the curve further, to where we could achieve zero shot performance on such tasks.

Figure 7: Comparison between FDM-1 finetuned on ~1hr of driving data and a model with only a vision prior on the same dataset.

Future Directions

Computer action used to be fundamentally data-constrained—expensive and not scalable. By both unlocking 11 million hours of internet-scale data and hour-long 30 fps video contexts, we are able to fundamentally push models from a data-constrained regime to a compute constrained regime. We are already seeing signs of our foundation model generalizing at small scales—from the model understanding CAD interfaces to driving a car in the real world—and we are confident that these improvements will continue with scale.

In the future we expect to scale our model to the entire 11 million hours of internet-data, continuing to saturate model evals. As we scale, we also expect reinforcement learning to work much better with our model’s diverse prior. There is significant evidence that foundation models can provide compounding effects to downstream reinforcement learning objectives. We expect to expand context in many ways and even further than we already have! Our goal is for the model to learn on the job with active exploration and adapt to new tasks over months-long contexts. Computer-use data specifically provides a good prior for this, with millions of examples of humans trying unique tasks, making mistakes, and learning over time. [15] 15. We expect our models to be especially good at research, due to much of computer use being using the internet. An interesting capability we expect is our model to watch a video, essentially “loading context”, to perform tasks.

We believe artificial general intelligence will be created within our lifetimes, and likely within the next decade. This work closes the gap on agentic behavior, but there’s a large amount of research left to be done to train aligned general learners. Standard Intelligence exists to solve this technical problem.

If you’re excited about our work [16] 16. We’re a small team of 5 at the moment, and believe strongly in hands on experimentation! , we’d love to hear from you at team@si.inc.

Collaborators

- Neel Redkar

- Yudhister Kumar

- Devansh Pandey

- Galen Mead